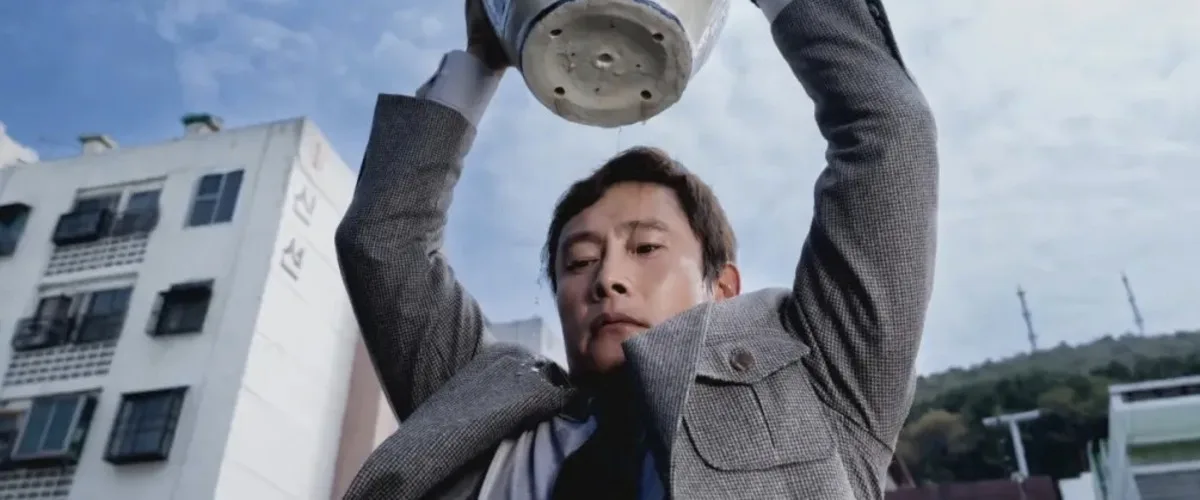

No Other Choice by Park Chan-wook (2025)

"The more it changes, the more it stays the same" - Jean-Baptiste Alphonse Karr

Watched by tomo hagan

It begins before you’ve even entered the cinema; the title, No Other Choice, is not some inside joke, or poetic aside, but the very axis upon which the film rotates. For those familiar with Park Chan-wook’s work, you’ve got a pretty good idea of what lead character Yoo Man-su’s (played by Lee Byung-hun) unemployment will drive him to, the raised eyebrow and flash of epiphany in his eyes a cheeky nod to the audience; a way of saying, “don’t worry, we’re right on schedule.”

The confidence to execute this moment of self-awareness, not only to turn to the audience, but to laugh with them too, to delight in its absurdity, is emblematic of Park Chan-wook as a filmmaker. Exacted with masterful control, his style centres upon gleefully leveraging the inherent drama of violence to explore social themes and issues. The more shocking and the more surprising, the better. The reputation he carries, big enough to pack out Dendy’s Cinema 1 on a Tuesday night (!), seems to be as something of a provocateur-entertainer bar none, to go places no one else dares. Though I do wonder if in this case style overshadows substance. What do we take away from a Park Chan-wook film? Is it the plea to wake up and hold onto the last traces of humanity fading from view, or is it the human head wrapped in cling wrap and its own vomit?

It can be both, sure, but my feeling is that one is a lot louder than the other. And that feeling has grown stronger since watching, especially so because the film doesn’t allow you much room for thought. It is so tightly controlled, each moment meticulously manufactured for a specific result, not unlike the AI-augmented digital technologies that are shown to have displaced a factory full of human workers at the end of the film. Upon reflection, I have come to wonder about the other choices. There was (apparently) no other choice, but what were the choices? Where were the choices?

My sense is that the experience of unemployment, technological or not, conjures an interrogation of one’s value, not just to their family or immediate circumstances, but to society as a whole. Where do I fit in? How can I contribute? What can I offer? Employment is not just a means to secure a livelihood but is the primary channel through which we can develop and practise and exert our competency. Or at least it used to be.

What is interesting to me about this subject matter, and what I liked about the film was its depiction of the lengths of rationalisation individuals can spin to keep their head afloat in a capitalist system whose only fidelity is to profit, never to human (and forget non-human) welfare. The inevitability that these rationalisations will pit people against people, eroding whatever once existed of mutual solidarity or communal feeling. Yes, there are parallels between Man-su’s experience and that of the less murderous, more common, unemployed person, and yes, there is value in extrapolating our rationalisations to their logical extremes, to show us how faulty they are. But are many people as proud or materially shallow as Man-su?

The film’s mantra, ‘no other choice’, seems to serve the narrative turns and overt violence, as much, if not more than being the foundational point of its social critique. Which leads me to wonder what it has to say? Is director Park’s incomparable enthusiasm for violence a social end in itself? To make seen what happens every day unseen? To shine light on violence not perpetrated immediately and physically, but that which happens gradually, insidiously, invisibly? In this case, to think about unemployment as a site of violence, with Man-su’s role as victim-perpetrator serving to implicate us as non-innocent actors. Because sure, you can point to corporate greed when they replace humans with robots, but they are only following the logic of the values we similarly perpetuate in our daily lives. The two, primary ideological faults being: a) linear, cause-effect thinking; the idea that our realities, actions, even minds, can be broken down into quantifiable, discrete processes, and as a logical corollary, b) every problem has a technological solution. Like the family home he bought back and can’t let go of, these are the values Man-su carries forward, the ones we all carry forward, despite bleeding from doing so.

What Man-su is doing is engineering a situation where he can achieve what he wants; it is his brain, his worldview, his unwavering inflexibility in trying to engineer his way out of a problem that inevitably evokes violence. This computational thinking, and experience of the world (if all you have is a hammer, everything is a nail) reduces the human to a line in a piece of the code; we have imagined ourselves to be quantifiable, and in doing so, accidentally made ourselves replaceable. The daughter's cello piece is a total rejection of this way of thinking - it is a provocation, a salvation, a way out, a way forth, a way back. It is an assertion of the human. A reminder that we are not cogs in a machine, nor lines of code. There is a messiness to us, an eternal element of not knowing.

Somewhere within that lies our commonality. Appeals to that commonality, and willingness to forgo some degree of individual convenience for the collective good were embedded within the development of our democracies, but they have been hollowed out entirely and as such, the practice of politics has been lost. This erosion of the political is entirely conspicuous by its absence in No Other Choice. Perhaps then, the real strength of the work lies in what it omits, whether planned or not. Man-su seems to be living in a vacuum, entirely on his own, helpless. We are not for a second meant to sympathise with the burden of responsibility that falls on his and his wife’s shoulders to sustain their family’s livelihood. Man-su’s stubborn, material individualism is taken for granted. It is not uniquely his own, simply his birthright. He is the poster child for the inevitable rot caused by the sweeping economic and social changes brought on by neoliberalism, where utopian ideals of individual self-expression and actualisation briefly stroked our egos, whilst public, democratic institutions were Ocean Eleven’d. Man-su is not a participant in the collective body, because there is no longer a collective body to participate in. No longer one to catch him.

No Other Choice, then, is a vision of the world not as it seems, but as it is. Corporations aspiring to the same ideal that existed since day dot, doing away with labour entirely, because like politics, labour is messy and riddled with inefficiencies. This ideal is more realistic today than ever, after neoliberalism’s successful, systematic dismantling of labour power and privatisation of public works. The hologrammatic projections of government can be turned off, leaving the individual, and their total, absolute freedom for self-expression.

No Other Choice is screening in most cinemas.

Pick of the Week

The surreal Australian indie feast that is 'A Grand Mockery' will screen at Golden Age on Saturday 31 January and Sunday 01 February. This is one that sits under your skin and one I've not stopped thinking about since I first saw it. Trust me, you don't want to miss out. Both screenings with be followed by a Q+A with the directors Adam C. Briggs and Sam Dixon. Details are here.

You Might Have Missed This...

New Releases: 29 January

- Addition (Marcelle Lunam) (AUS)

- It Was Just An Accident (Jafar Panahi)

- Blue Moon (Richard Linklater)

- Send Help (Sam Raimi)

- Iron Lung (Mark Fischbach)

Looking for the weekly guide? It's relocated into the regular newsletter. Subscribe to get curated recommendations or follow the Fleapit on Instagram to see the highlights of each week!

Comments ()