on this and that, #1 Sep 2025

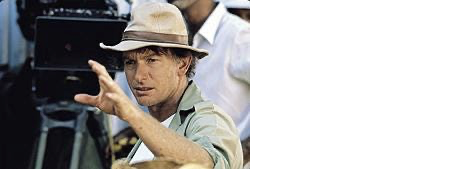

Now I don’t mean to be a hater, but I did not expect such a strong sense of pained self-awareness in Gallipoli’s nationalist self-determination from a man who looks like this...

on Gallipoli and National Self-awareness:

Introducing a new column on the Fleapit called 'on this and that' by regular-guest contributor Helena Williams. This is a fortnightly series diving into the back catalogue of Australian cinema with a personal lens and finding the relevance to today. Enjoy! - from Matthew (founding flea)

Now I don’t mean to be a hater, but I did not expect such a strong sense of pained self-awareness in Gallipoli’s nationalist self-determination from a man who looks like this:

Given, he did look more like this when the film was in production:

But you get my point.

Like I said, I hate to be presumptuous, but there was something about a middle-aged white man in the 1980s that didn’t scream “woke” to me. Boy was I wrong, and from the bottom of my heart, Peter Weir (who is definitely reading, if you are not Peter Weir, best to stop reading now),

I am deeply sorry for underestimating you.

An Australian classic (that I definitely watched on my own accord and was definitely not forced to watch at uni), Gallipoli (1981), is arguably one of the most influential works on the historic event. Both the campaign and the film itself are held in incredibly high regard, contributing a significant weight to our perceived Australian national identity.

Many articles examine Gallipoli (1981) in its significance to shaping Australian nationalism, as well as some exploring the homoerotic themes present throughout the film. However, today, I would like to address the film’s painful self-awareness in its subtle exploration of Australia’s own colonial history. This might be a reach, but one scene in Gallipoli struck me in particular, due to the stark parallels it draws to the representation of imperialist Britain’s brutality in the final scenes of the film.

Whilst in Cairo, preparing for Gallipoli, a proud Barney says, “Have a look at this, fellas, over a thousand years old”, as he whips out what he believes to be a prized ancient artefact, found at a small Egyptian market. Billy immediately shuts him down by producing an identical figurine, claiming he paid significantly less. Considering this “theft” and “against Australian values”, they all return to the market stall and demand their money back. In the final moments of this scene, Barney, having made a mistake, admits they destroyed the wrong stall, forcing us to quietly acknowledge the purposeless destruction and violence we just witnessed, in thematic alignment with the entire film.

The market-stall scene begins with “We’re not just soldiers, we are diplomats for our country”, a statement that, ironically, is immediately followed by the mass, unnecessary destruction of the merchant’s goods and stall. The scene is playful, with the boys laughing, but at what cost?

After viewing, I couldn’t help but question WHY. WHY would he choose to have this scene in the film? WHY would he include the final admission that the violence we witnessed served no purpose (does it ever, but that’s a whole other article), and then WHY make the Australians the perpetrators of said violence? Isn’t this whole film about hating the British??? I thought we were the good guys??? I thought we were a separate entity from the British (despite behaving in a very similar way).

At the time the film is set, more than 90% of Migrants to Australia were from England in the 8 years prior to 1914. That being said, many Australians held Britain in high esteem, calling it the “Mother Country”. This scene also serves to shed light on the admiration of Imperial Britain from Australians at the time, and makes the young Australian men’s admiration evident through their replication of violent behaviour.

Throughout the scene, the boys make numerous references to how things are done “back in our country,” clearly alluding to their notion of Australian superiority. In my opinion, it is Weir’s intention here to highlight Australia’s own dark history and shed light on the falsified “underdog” identity we so frequently were (and still are) drawn to in our national cinema. In this instance, the Australians are not the underdog, and, although larrikin in nature, the characters perceive themselves to dominate over a culture that is different from their own.

And this is where, Peter (first name basis), I will not renounce your bestie status. The viewing discomfort I felt during this scene returned on a greater scale when the British ordered thousands of men to their deaths later on in the film; the market scene almost foreshadowed what was to come. I felt primed to reflect on not only the terrible tragedy of Gallipoli, but also the ways in which Australian history has its own moments of diabolical destruction.

The irony of the film’s purpose being to forge a uniquely “Australian” identity separate from British colonisation is not lost on me, and I don’t think it was lost on Weir either. Despite being integral to the cinematic fabric of Australia, this film serves as a commentary on not only the horror of Gallipoli but also on every individual involved in the massacre of thousands of people.

references

https://research.avondale.edu.au/server/api/core/bitstreams/3c504cee-b62d-452f-9a56-fbcd83b624f8/content

https://anzacportal.dva.gov.au/wars-and-missions/ww1/military-organisation/enlistment#:~:text=Widespread%20empathy%20for%20Great%20Britain's,England%20'the%20mother%20country'.

Comments ()