28 Years: An Elegy for England

How do you eradicate a virus which consumes the future and grips to the past?

28 Years Later and its sequel The Bone Temple places British anxieties, paranoia and contemporary politics against a zombie apocalypse. Across the two films, typical zombie tropes are flipped and subverted to not only expand the world built across the series of films, but to interrogate our own biases. What emerges is the tale of a dying empire and how those caught within the death-spiral respond with competing messages love or hate.

Written by Alex Garland and directed by Danny Boyle, the original 2002 film, 28 Days Later, introduced London as a deserted, collapsing city. In an iconic early scene, Cillian Murphy's character, Jim, walks across an empty Westminster Bridge, confused as to what has unfolded since waking from his coma. What has occurred is that the island-state was stricken by a rage-inducing virus turning humans into fast-moving, flesh-eating creatures within seconds of infection. Its sequel in the hands of two different creators, 28 Weeks Later, saw an international military force unsuccessfully attempt to form a safe zone in London free from the infection.

The third film 28 Years Later, helmed again by Garland and Boyle, moves to the countryside of England, a place full of beautiful landscapes and horrifying creatures. Decades after the rapid spread of the infection, the world has decided to form an exclusion zone around the United Kingdom. No one goes in. No one gets out. What has occurred is not a slow eradication and dying out of the virus as hoped but instead a mutation and evolution. No longer just fast-moving zombies but now there are slow-crawlers and Alphas, the leaders of the pack with seemingly increased strength and intelligence. The Bone Temple, written by Garland but directed by Nia DaCosta, fleshes out the story of those in the third film to chart a horrifying tale of what humans are capable of in the face of crisis.

Return to a great Britain

A small, civilised community lives on Lindisfarne; a small island naturally protected from the Great British mainland via a causeway which floods each high tide. It is a mixture of medieval and post-war British iconography. Children learn to use bows and arrows, boot-stomping ballads are sung in the town hall, apples are a precious commodity. And yet, the Queen's portrait hangs on the wall, the St George flag waves atop the pole and traditional lessons of community-building are taught. It is a society which has regressed and looked to the past as a means of survival. It does not seek to build a world for the future but instead finds solace in old traditions. It has manifested what Brexiteers so desperately pursued in 2016 - a homogenous society built on traditional values which harks back to the 'great' times of England.

And if Lindisfarne is the idealised Great Britain of Brexiteers, then does that make the zombie-infested mainland the savage wasteland of Europe? In the eyes of the residents of Lindisfarne, the mainland is a battlefield, yet it is one they cannot be fully isolated from. No matter how much they desire independence, they still rely on the mainland for resources, for medicine, for fuel and for glory.

As our protagonist Spike, led by his father Jamie, cross the causeway for Spike's rite of passage hunting trip, a montage of footage from WWII and Laurence Olivier's Henry V plays accompanied by a Taylor Holmes’ recitation of the Rudyard Kipling poem, Boots. Like those in the footage and eulogised by Kipling, Spike and Jamie march into a land of death. This imagery forebodes what is to come, while also linking to how these devastating moments of history have been mis-remembered as sources of pride and triumph by nationalists. In their regressive pursuit for power, the nationalists have forgotten, either wilfully or ignorantly, that these myths come hand in hand with mass casualties, innocent victims and purposeless murder.

One such victim of this isolation is Isla, Spike’s mother. Afflicted from an unknown illness affecting her mind and body, she is contained to their upstairs bedroom to suffer. In one particularly striking sequence, through infrared vision, we witness her floating in the ocean, like a mythic being, isolated, lost and misunderstood. Medicines may be available to her on the mainland, but no one is willing to assist her except Spike. They are forced to venture out to the mainland to find Isla support because of the village’s isolationism, to enter the unknown in hope for a better life.

If you like this piece, consider signing up for more

And We Are Alike

At one point in their journey through the countryside, Isla and Spike come across the Angel of the North. Isla recounts visiting the monument as a child with her father who explained that, just like Stonehenge, “it would stand like this forever…so when you look at it, you’re seeing into the future.” Two monuments of the English countryside, both have been co-opted in recent years for nationalistic endeavours. They have been used as symbols of the past to justify contemporary regressivism while neglecting that these monuments look to the future. Dr Ian Kelson’s Bone Temple becomes the third monument in this landscape to stand at the intersection of the past and the future.

Dr Kelson is the isolated, iodine-covered man in the pastures. With no patients to treat, he has seen it his duty to become the caretaker to the dead. With his furnace and water pump, Kelson collects corpses, burns them, washes the bones and finds a place for their remains amongst the temple of bones. Upon meeting Isla and Spike he reminds the pair that humans and zombies are alike in their construction. Each skull in his tower spoke and cried and ate and laughed and kissed. Piled atop each other, there is no distinction between the healthy and the infected. Each is given a space next to the other in his sacred memorial. In this way Kelson’s work is imbued with a reverence. It is a reminder to the living and a mark of respect to the dead. Like Stonehenge and the Angel, the Bone Temple will remain standing after the architect’s death and will strike fear and awe in all that come across it.

The motto of likeness is manifested most strongly in the unlikely partnership of Dr Kelson and the Alpha Samson. With the delicate touch of a doctor treating a complex patient, Kelson treats Samson with humanity and dignity, a right so rarely afforded to the infected. They reach a mutually beneficial arrangement based on what they have in common, not on their difference. This is perhaps the greatest contribution to the zombie genre made by these two films. Dr Kelson represents a radical, empathetic shift in how we perceive the infected. With a warped blend of wit and weight, Ralph Fiennes breathes life into Kelson and meets the seriousness of the moment. Surrounded by reminders of death for decades, he sees the sacredness in every life.

How’s About That, Then?

If Kelson represents the beauty of life through death, Jimmy Crystal is his antithesis. Leading a pack of tracksuit-wearing, blonde-wig clad fighters all named variations of Jimmy, Crystal is a harbinger of death. The son of a church minister, Crystal was a young boy when the infection first spread. In the intervening years his memory of religion and of his father’s confusing open-armed response to the outbreak has mixed with hallucinatory experiences, resulting in a version of Satanism. The pack wander the British landscape hunting for victims to sacrifice to Satan, who Jimmy believes is his father. In increasingly gruesome sequences we witness the torture of a family of survivors. The skin peeling and harrowing screams are even too much for Crystal’s followers and yet they continue their mission out of fear for being the next sacrifice if they speak out of line. More broadly, Jimmy’s Satanism is akin to the villainous manipulation of those less fortunate by powerful individuals in our society. Leaders spreading hatred and vitriol against others, encouraging division and violence as a means of exerting control and demonstrating power.

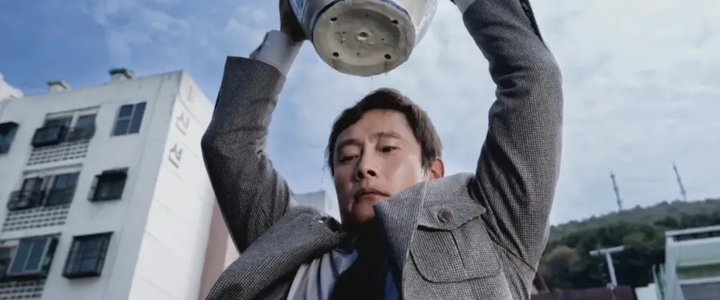

The sadism of Jimmy and his pack is reinforced by their adoption of aesthetics drawn from Jimmy Savile. The eccentric host of Top of the Pops and Jim’ll Fix It, Savile became an icon of British pop culture and charitable work. After his death, hundreds of allegations of sexual abuse emerged, with investigations concluding that he was perhaps the most prolific sexual predator in the United Kingdom. These revelations however emerged in 2012 and in the history of 28 Years would never have come to light. Not only do the Jimmys unknowingly cling on to a destructive cultural icon, reflecting a selective memory of British history, but mirror the predatory behaviour of Savile through the hunting of innocent victims and demanding of charitable acts. It is an effective addition to the world which manifests the hatred which drives Crystal. The through line drawn between Savile and Crystal is a reminder that Britain’s history is steeped in violence, abuse and the corruption of innocence, which is consistently overlooked in the pursuit of comfort in tradition.

Foundations and Hallucinations

During a conversation between Kelson and Crystal, the pair discuss their memories of what life was like before the infection. While echoes of objects (cell phones, television, personal computers) sit on the periphery, what Kelson is certain of is the certainty of daily life. He remembers most clearly that there was a solid foundation to the world on which we could rely. When that foundation was removed, what emerged was a group of subjective experiences each with their own truth of how the world worked. None which shared a common understanding. All which floated between the past, present and future. These collective, fragmented hallucinatory experiences are spotted through the films. Isla, in her medical condition, hallucinates dial-up modems, ringtones and a tidy suburbia. Crystal, in his cult, hallucinates voices from Satan demanding sacrifices and death to seek redemption from the plague sent by God. Samson, in his infection, hallucinates the healthy as crazed individuals and dreams of his family on the train in the countryside.

Somewhere in our recent history, the solid foundations of our society eroded and what rose in its place were similar hallucinations of how we believed the world worked. In the final moments of The Bone Temple, two characters discuss the politics of inter-war Europe. Their focus is the ill-fated, heavy-handed response by the victorious powers to punish the losing nations. The seizing of land, extremely high reparations, military restrictions and burdening of blame laid the foundations of resentment and vitriol for fascism, nationalism and populism to grow. The hallucinations of today are akin to the hallucinations of 1930s mainland Europe. One day, Britain, America and much of the West will awake from its hallucination, and the question faced then is how to, like a virus, eradicate an idea. Jimmy Crystal provided one pathway: a doubling-down in the wafer-thin belief that force and power will lead to redemption. Dr Kelson provides another: that of radical empathy and understanding.

The final line of The Bone Temple, delivered like a warm hug, points to a potential for redemption and healing for both human and infected in Britain. The question remaining to be answered is this: will the real world respond in the same way?

Comments ()